Partitioning Africa: The 1884-1885 Conference of Berlin

Africa raped and partitioned: the 1884-5 Congress of Berlin

_____________________________________

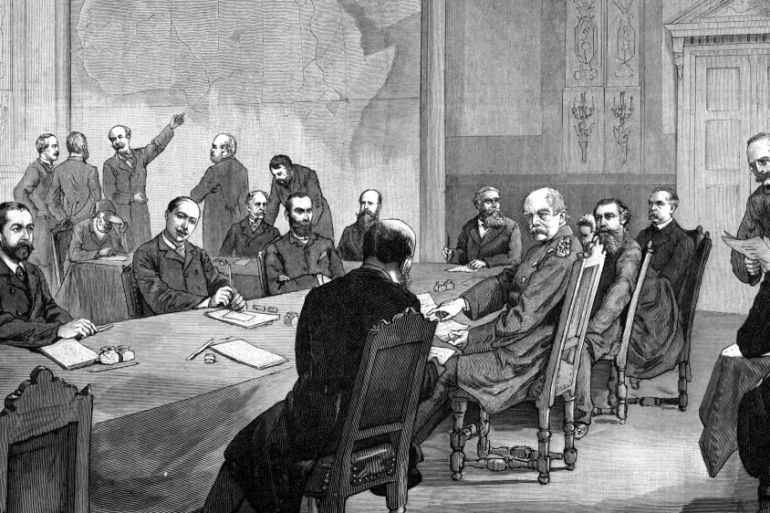

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries there were two international conferences which decided the fate of two of the world’s regions for more than a century: The Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 carved up Africa between rival European colonial powers (with no Africans represented) and what is referred to as the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1917 that divided up the regional remains of the Ottoman Empire. In both cases, borders encircling what are today national entities, were created that had nothing to do with local/regional economic, political or cultural realities. The article below is a fine summary of one of them, the Berlin Conference of 1884-5). In both cases, fine examples of Colonialism and Neo-Colonialism in action.

_____________________________________

Colonising Africa: What happened at the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885?

This month marks 140 years since Western powers sidelined Africans and carved up ‘ownership’ of the continent among themselves.

More than the ongoing trade between the two continents that had run for decades, though, the Europeans wanted direct control of Africa’s natural resources. In addition, these countries aimed to “develop and civilise Africa”, according to documents from that period.

Squabbles soon erupted in Europe over who “owned” what. The French, for example, clashed with Britain over several West African territories, and again with King Leopold over Central African regions.

No African nations were invited or represented.

What was the Berlin Conference about?

In November 1884, German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck took up the task of calling for and hosting the conference in Berlin at the Reich Chancellery, his official residence on 77 William Street.

For months leading up to that, French officials, in missives to Bismarck, had raised worries about Britain’s gains, especially its control of Egypt and the Suez Canal transport route. Germany, too, was worried about conflicting areas with the British, such as Cameroon.

The Bismarck-led talks lasted from November 15, 1884 until February 26, 1885. On the agenda was the clear mapping and agreement of who owned which area. Regions of tax-free commerce and free navigation, particularly in the Congo and Niger River basins, were also to be clarified.

Who attended?

Ambassadors and diplomats from 14 countries were present at the meeting.

Belgium’s King Leopold also sent emissaries to secure recognition of the “International Congo Society”, an association formed to establish his personal control of the Congo Basin.

No African leader was present. A request by the Sultan of Zanzibar to attend was dismissed.

- Austria-Hungary

- Denmark

- Russia

- Italy

- Sweden-Norway

- Spain

- Netherlands

- Ottoman Empire (Turkey)

- United States of America (US)

What was the outcome?

Over three months of haggling, European leaders signed and ratified a General Act of 38 clauses that legalised and sealed the partition of Africa. The US ended up not signing the treaty because domestic politics at the time began to take an anti-imperialist turn.

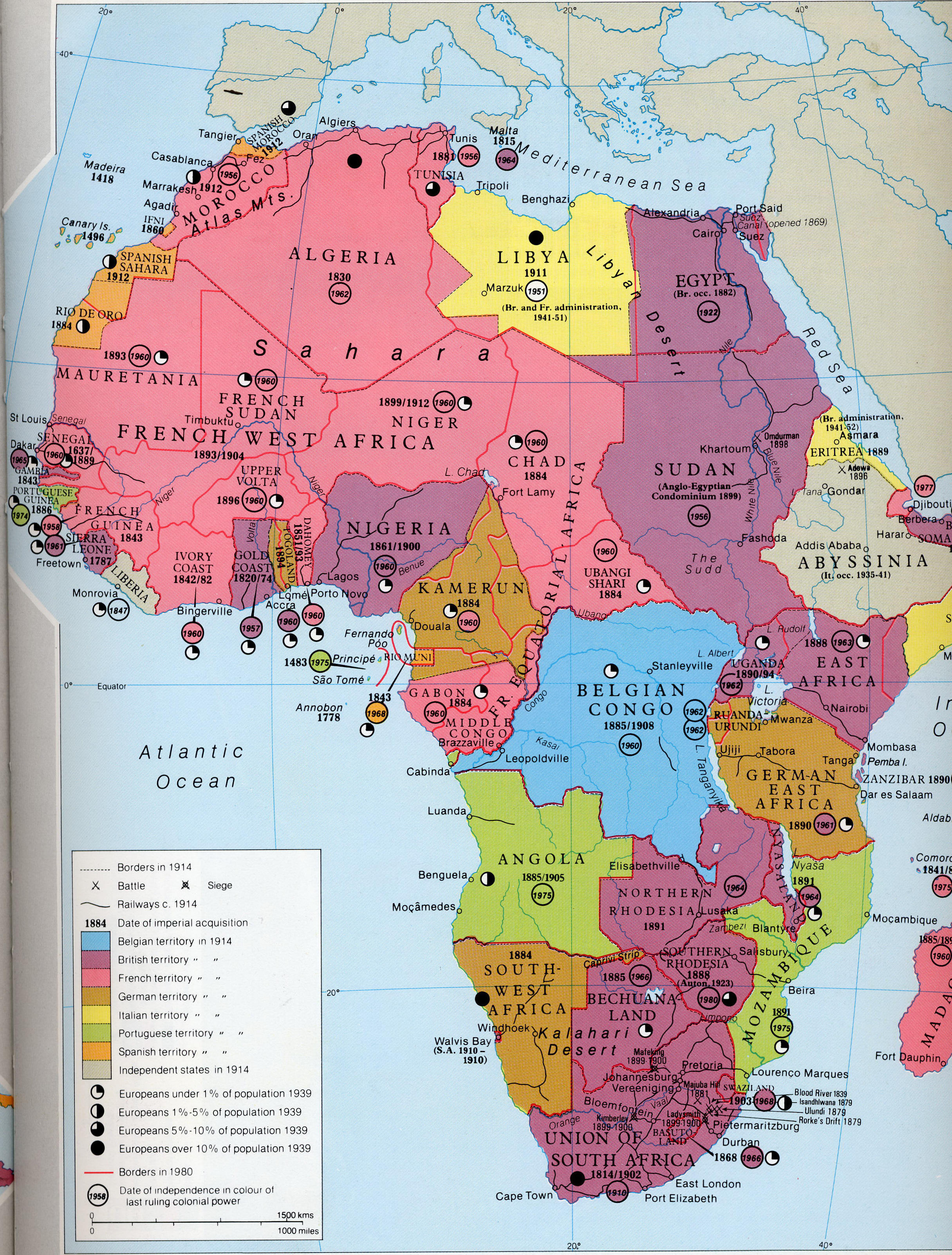

- The colonising nations drew up a ragged patchwork of new African colonies, superimposed on existing “native” nations. However, many of the actual borders recognised today would be finalised at bilateral events after the conference, and following World War I (1914-1918) when the Ottoman and German Empires fell and lost their territories.

- In addition, the General Act internationalised free trade on the Congo and Niger River basins. It also recognised King Leopold’s International Congo Society which was controversial because some questioned its private property status. However, Leopold claimed he was carrying out humanitarian work. Areas that ended up under Leopold, known as the Congo Free State, would suffer some of the worst brutalities of colonisation, with hundreds of thousands worked to death on rubber plantations, or punished with limb amputations.

- Finally, the Act bound all parties to protect the “native tribes … their moral and material wellbeing”, as well as further suppress the Slave Trade which was officially abolished in 1807/1808, but which was still ongoing illegally. It also stated that merely staking flags on newly acquired territory would not be grounds for ownership, but that “effective occupation” meant successfully establishing administrative colonies in the regions.

Who ‘got’ which territories?

Western “ownership” of African territories was not finalised at the conference, but after several bilateral events that followed. Liberia was the only country not partitioned because it had gained independence from the US. Ethiopia was briefly invaded by Italy, but resisted colonisation for the most part. After the German and Ottoman empires fell following World War I, a map closer to what we now know as Africa would emerge.

- France: French West Africa (Senegal), French Sudan (Mali), Upper Volta (Burkina Faso), Mauritania, Federation of French Equatorial Africa (Gabon, Republic of the Congo, Chad, Central African Republic), French East Africa (Djibouti), French Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire, Dahomey (Benin), Niger, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, Libya

- Britain: Cape Colony (South Africa), Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), Bechuanaland Protectorate (Botswana), British East Africa (Kenya), Northern Rhodesia (Zambia), Nyasaland (Malawi), Royal Niger Company Territories (Nigeria), Gold Coast (Ghana), Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (Sudan), Egypt, British Somaliland (Somaliland)

- Portugal: Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique), Angola, Portuguese Guinea (Guinea-Bissau), Cape Verde

- Germany: German Southwest Africa (Namibia), German East Africa (Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi), German Kamerun (Cameroon), Togoland (Togo)

- Belgium: Congo Free State (Democratic Republic of the Congo)

- Italy: Italian Somaliland (Somalia), Eritrea

- Spain: Equatorial Guinea (Rio Muni)

What did the conference change?

Historians point out that unlike what is widely believed, the Berlin Conference did not kick-start the colonisation process; instead, it accelerated it.

While only about 20 percent of Africa – mainly the coastal parts of the continent – had already been staked by European powers before the conference, by 1890, five years after it, about 90 percent of African territory was colonised, including inland nations.

But there are also those, like researcher Jack Paine, who say the conference itself was of little consequence: That some African countries were already mapped out in earlier expeditions, and that many of the borders we recognise now would not be formalised until much later.

“The Conference itself established little in the way of making states, with the lone exception of creating today’s Democratic Republic of the Congo,” Paine, a political studies lecturer at Emory University told Al Jazeera, referring to the then Congo Free State.

“The reason the conference convened in the first place was because Europeans had already initiated a ‘scramble’ for African territory,” he added. “It is difficult to give much credence to the standard idea that the Berlin Conference was a seminal event in the European partition of Africa.”

Paine, and many other political scientists, however, agree that colonisation determined the future of the continent in ways that continue to have profound geo-political effects on today’s Africa.

Even after African leaders successfully fought for independence and most countries became liberated between the 1950s and 1970s, building free nations was difficult due to the damage of colonisation, researchers say.

Because of colonialism, Africa “had acquired a legacy of political fragmentation that could neither be eliminated nor made to operate satisfactorily”, researchers Jan Nijman, Peter Muller and Harm de Blij wrote in their 1997 book Realms, Regions, and Concepts.

Following independence, civil wars broke out across the continent, and in many instances, caused armies to take power, for example in Nigeria and Ghana. Political theorists link that to the fact that most groups were forced to work together for the first time, causing conflict.

Meanwhile, military governments would continue to rule many countries for years, stunting political and economic development in ways that are still obvious today, scholars say. Former colonies such as Mali and Burkina Faso, both led by the military, have now turned against France because of perceived political interference they say is an example of neo-colonialism.

In a famous quote, Julius Nyerere, the former Tanzanian president, articulated what researchers agree is the current state of Africa: “We have artificial ‘nations’ carved out at the Berlin Conference in 1884, and today we are struggling to build these nations into stable units of human society … We are in danger of becoming the most Balkanised continent of the world.”