Under The Bombs, a film by Philippe Aractingi

____________________________________

Here in the USA, the horrors of war – any war – are muffled by governments hiding their complicity and a compliant media. Most “really don’t get it” when it comes to war as there has been – other than Pancho Villa’s brief 1916 attack on Columbus, New Mexico and a few Japanese air balloon bombs sent during WW2 by Japan – virtually no war fought on American soil since the Civil War, now 160 years ago. Yet war is rampant the world round, especially in the Middle East where it has become normalizsd to such a degree that it competes daily with the weather and the latest government scandal. This is not the case for the peoples of the Middle East, the suffering masses in Gaza, the West Bank and Lebanon. Yet there are some movies that shatter this complacency, and remind us just how horrible, how destructive war is today. One of these films is Philippe Aractingi’s “Under The Bombs” about the 2006 Israeli military offensive and bombing campaign into Southern Lebanon. What this film does, and does frankly as well as a film can do, is to humanize this war story.

____________________________________

The library at Regis University, walking distance from our home, is a friendly place, in many ways open to the public although it seems that many neighbors are unaware of the resource “just next door”. A Jesuit university with a solid academic record, it has been the academic home of a number of close friends who taught there, among them the late Jamie Roth, Byron Plumley, Alice Reich to name a few. All are long retired. The Regis library has an extensive video/dvd collection which I enjoy perusing. One video that caught my eye last week was “Under The Bombs” directed by Lebanese director Philippe Aractingi. I have watched over the past few days and was moved by its essential subject matter: what it is like for peoplem civilians living in the midst of war, in this particular case, the 2006 war in Lebanon.

No i”Under The Bombs” not about Gaza … but in a way it is.

” Under The Bombs” was filmed in the midst of Israel’s 2006 attempt to “mow the lawn” in S. Lebanon, to strike a blow against Hezbollah there. Instead, meeting with fierce resistance that included a Hezbollah missile cutting an Israel war ship in the eastern Mediterranean in half, Israel was forced to withdaw. It called Washington asking to sue for peace, its troops and tanks returning south of the Lebanese border. While historians argue as to “who won” … there is doubt that in 2006 Israel got the kind of bloody nose it was unaccustomed to – a prelude to the failure of its military operation in Gaza. But the price that Lebanon had to play for defending its sovereignty was very high.

According to Google’s A.I. which pops up as a result of a search:

The war inflicted immense damage on Lebanon. An estimated 1,191 to 1,300 Lebanese people were killed, mostly civilians, and approximately one million were displaced. Vital civilian infrastructure was destroyed, including the Beirut airport, ports, roads, bridges, and power plants, with total damage estimated in the billions of dollars.

Not being a fan of A.I. and hardly using it, still, other than the fact that the casualty figures are pathetically undercounted, this description of the damage inflicted on Lebanon is accurate. How many uncounted deaths “under the rubble” as in Gaza? How many lives emotionally, physically, torn apart among the civilian population that are not counted among the war dead, or poorly counted? How many who died after the fighting was over from starvation, wounds suffered during the bombings, from suicide because of the loss of home and family?

A Human Rights Watch analysis of the war adds some texture to these dry facts:

Israeli warplanes launched some 7,000 bomb and missile strikes in Lebanon, which were supplemented by numerous artillery attacks and naval bombardment.[1] Israeli airstrikes destroyed or damaged tens of thousands of homes. In some villages, homes completely destroyed by Israeli forces numbered in the hundreds: 340 homes completely destroyed in Srifa; 215 homes completely destroyed in Siddiquine; 180 homes completely destroyed in Yatar; 160 homes completely destroyed in Zebqine; more than 750 homes completely destroyed in `Aita al-Sha`ab; more than 800 homes completely destroyed in Bint Jbeil; and 140 homes completely destroyed in Taibe. The list throughout southern Lebanon is extensive.

Point made – although brief, Israel’s military campaign in Lebanon that included a bombing campaign throughout the country was unspeakably horrible for the civilians living through it, the damage inflicted, physical, emotional was horrific despite its brevity.

2.

How to interpret the more profound essence of the Human Rights Watch analysis just above? To translate it into a human emotional level? How to live through Israel’s punishing bombing campaign which, like so many others it has unleashed on the Palestinian and other Arab peoples, caused untold and unappreciated human physical and emotional damage? No question that in making “Under The Bombs” that Philippe Aractingi tried to communicate with his global audiences.

But before delving into the film’s disturbing content some, a few related comments:

Having had the good fortune to have lived abroad for nearly ten years (France, Tunisia, Finland) I have found myself in countries that have all experienced the impact of war. Of course, other than a month trip to Syria and Lebanon in 1981 where, in both countries, the war with Israel was on-going, mostly what I experienced was the aftermaths of war and not war itself.

For France there is the experience of World Wars One and Two, and its cruel anti-colonial wars – Algeria, Madagascar, IndoChina, Cameroons. Tunisia’s 20th century history was marked by the struggle against French colonialism which was often far more cruel and violet than is often described these days. As for Finland, for 600 years colonized by Sweden, the 20th century was characterized by dramatic political swings, civil war, the Winter War against the USSR followed by its alliance with Nazi Germany in WW2, an alliance that broke down after Stalingrad and Kursk when Finland switched sides.

What I noted in all three foreign countries where I lived is that the consequences of war live on long after the fighting itself is over and that the suffering on all sides lingers for generations.

A few examples from my personal experience suffice. These have stayed with me through the years, and, there are many more.

- In Prague in 1983, participating in a peace conference there, an older woman daycare center employee was still terrified that “the Germans might be coming back”, that was 42 years after the war’s end. She appeared terrified and kept on repeating how horrible WW2 had been in (what was then) Czechoslovakia. I have never forgotten the fear – the utter terror – in that woman’s face.

- On a bus trip in Eastern Algeria in 1987, we pass through a town called Setif. Of course, until then I had never heard of it. There was an enormous monument to the fallen in the independence war against France. But the events – the slaughter – that the French had carried out in the Setif-Guelma regions had happened not after 1952, the beginning of the armed struggle, but nine years prior, in the summer of 1945. In order to put down an incipient expression of Algerian nationalism, the French military massacred somewhere around 35,000 Algerians. Learning about Setif impressed upon me the high price in human life that anti-colonial struggles would have to pay – and continue to pay – for independence from colonialism, neo-colonialism.

- In 1981, I am at a party of an Iraqi born friend in Beirut a very convivial affair. But I hear machine gun fire that sounds d very close at hand. Admittedly frightened by the sound, I ask my host-friend if we should seek shelter. He stops, listens and says something to the effect “No worries; it’s a block away; nothing to be concerned about”. No one else in the room shows any signs of concern. These are people who have learned how to live in a warzone.

There were other experiences, all far from home: a 1960 visit to the French town of Oradour, a 1986 visit to the Nazi concentration camp at Sachenhausen, to the Piskaryovskoye Memorial Cemetery in what is now St. Petersburg commemorating the slaughter – genocide by bombardment and starvation of mnore than a million Soviet citizens,led Sand Creek, another to Topeka where an entire thriving Black community was wiped out in a racist orgy back in 1919, a visit to Hiroshima. And now, second to none: watching on social media the U.S.-Israeli genocide being perpetrated in Gaza and increasingly also in the West Bank.

Why list these personal experiences?

Because through them I learned to appreciate both the horrors and the pervasiveness of war. But for many Americans, I would guess more than the majority, war is unreal, sanitized and distorted on the news, completely reshaped in cinema, made into something akin to a video or board game, a spectator sport. It might be serious for others, but not for us (although there is an ample number of excellent anti-war films of which “Under The Bombs” is one).

The last major war on U.S. soil is more than 150 years ago, the Civil War. Unlike much of the rest of the world, with few exceptions, so many Americans are oblivious to the reality of war. War is out of sight, out of mind, something that happens in foreign places, but not here. Yet, it’s not that we don’t know violence. Ours, the USA is a very violent country as any serious study of our past indicates. This becomes a serious problem where it concerns American foreign policy.

How to pierce this obliviousness, this incredibly shallow understanding of war, its dangers, its consequences so prevalent among the American population? How to share the understanding that horrible, unbelievably horrible things are happening in the world we live in – yes, in Gaza where the horrors reach unspeakably racist and disgusting levels?

I have been grappling with this dilemma – the American amnesia concerning war for decades with friends and colleague, these past decade? It is as if the war in Vietnam, my generation’s “war to end all wars” never really ended, now a half century after the U.S. suffered a historic defeat there.

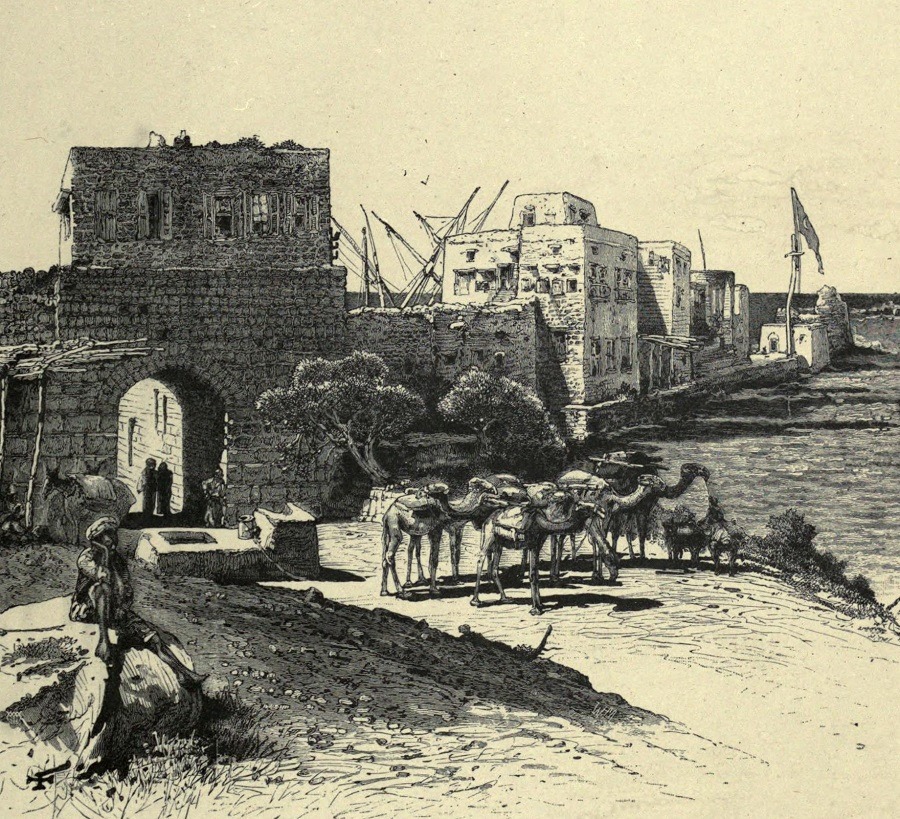

Tyre Lebanon. 1800s. Ottoman Imperial Archies.

3.

“Under The Bombs” is a film that follows a Lebanese woman, Zeina, a Moslem, from a prosperous family living in Dubai. Although it is not explicited stated (as I recall), she seems to come from a Lebanese Shi’a family. She hires a Christian taxi driver, Tony, for the dangerous mission of finding her young son caught in the Israeli bombing campaign in Lebanon’s south. Tony comes from a Chritisan family in the south; he has a brother who joined a pro-Israeli Christian militia. Together, in the midst of the bombing and destruction, they head south in Tony’s Mercedes taxi to look for Zeina’s son.

Interesting enough, Zeina and Tony are actually the only professional actors in the film, the rest being interviews with real survivors with real footage of the destruction Israel rained down on Lebanon. Over the course of the journey and the film, the two move from intense suspiciousness of one another to an understanding that they share a powerful bond – both, a Moslem-Shi’a woman and a Lebanese Christian man whose French is stronger than his Arabic, are victims of war. The growing solidarity and ultimately trust that develops between these two, who overcome, or, perhaps more accurately, begin to overcome their mutual prejudices is one of the richest themes of the film.

The film begins with an Israel bombing of the hills just east of Beirut but continues as a kind of road movie about their journey through a landscape devastated by war in the areas south of Beirut to Israel’s northern border. Tony’s taxi takes Zeina through a bombed out landscape both along the Lebanese coast down to Tyre and then inland to Christian towns near the Syrian-Israeli border as Zeina frantically searches for her sister and son. But Zeina is too late as her sister and son are already dead, buried “under the bombs”, ie, under the rubble, and so badly so that retrieving their bodies is not possible. Still a long the way Zeina and Tony, whose relationship warms as the journey continues, meet the wondrous people of southern Lebanon, themselves survivors who have endured loss and trauma which is a key element of the film.