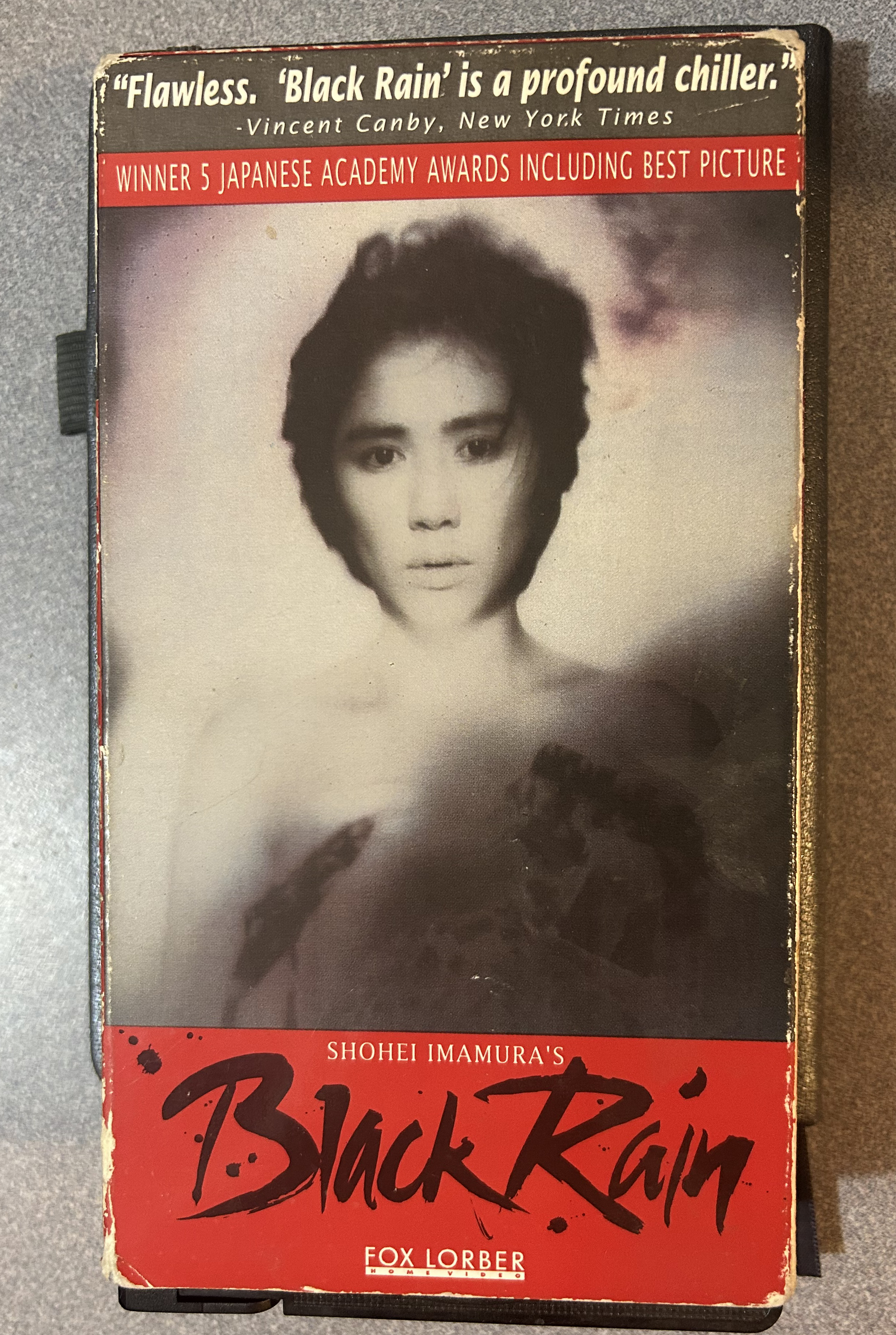

Happy Hiroshima Day – “Black Rain” – Shohei Imamura’s Hiroshima Masterpiece

Shohei Imamura

Shohei Imamura

Generally unknown to the public in the United States, but (I am told) loved in Japan, Shohei Imamura’s films are about as good as it gets. If Samuel Fuller’s films are about a disharmonious world just underneath the surface of Doris Day’s smiling face (she took showers 3 and 4 times a day – very unhealthy), the deeper themes in Imamura’s films gravitate around the possibility of reconstructred `shattered harmony’. There is a concept in Japan known as `wa’ – which roughly translates as `harmony’. People strive for harmony both with nature and among themselves. Imamura at his best (Black Rain, Ballad of Narayama, The Eel) looks at the lives of people in which harmony has been destroyed. It seems that he is often posing the question: once destroyed, can the harmony somehow be restored. It is not a new or even that unique notion – very common among traditional peoples – hunter-gatherers and farming peoples and explored and developed in the most profound manner by Joseph Campbell in his writings.

In `Black Rain’ (NOT the picture with Michael Douglass with the same title but Imamura’s) harmony is shattered rather decisively by what today is described as `a nuclear device’ . The film begins with the bombing of Hiroshima, the U.S.A.’s warning to the world: we did it to Japan twice and we’ll do it to YOU if need be.

There are some scenes of the devastation – which should be watched even if causes people to squirm as it does me – but in its relation to the story, more important is a family outside of Hiroshima on a boat on whom radio active rain – the black rain falls.

Although the opening is rather dramatic `Black Rain’ is, like life itself, mostly long and slow moving, more than 2 hours. Most of the film is about the aftermath of the bombing with the main theme fast emerging: how do people survive – those who are not vaporized – the impact of a nuclear explosion. The answer of course is not easily. Yet the whole film explores the effort to do just that. Everything from modern medicine, traditional medicine, psychology, love, the reconstruction of the family come into play.

Over the course of the movie a relationship develops between a badly mentally scarred war veteran – the memory of his buddies crushed by tanks – and a young woman, with nuclear sickness emerges. He’s a victim of conventional, she of nuclear war, the old and the new forms of devastation if you like in 1945. They find each other and share, ever so briefly, a moment of love and human connection – that which the war had tried to destroy.

`Ballad of Narayama’ is an exquisite story of traditional Japan just before the period of the country’s rapid industrialization. It takes place in a tiny mountain village with barely enough food for the villagers to eke out a living. Life there is not without its cultural patterns and rewards, but it is mostly harsh, just how harsh comes through at the outset as villagers gossip who it was who threw a baby to die out in the fields. Another mouth to feed. The story gravitates around the relationship between a mother and her eldest son. Plagued with food shortages there is a tradition in the village that when old people reach a certain age that their children, their oldest sons in particular, accompany their parents to the top of a mountain – Narayama – to die. It is all carefully arranged. No one tells a person when their time is up, each one decides on their own. There is a formal ceremony with the village elders, the person – in this case the mother – tries to tidy up earthly affairs, relations with family and friends – and then that final journey begins.

What gives the film such power is the moral struggle of the eldest son, who despite tradition, and what is obviously great love for his mother, resists what is his cultural responsibility of accompanying his mother to her death. In the end all these people have – that keeps them together is their culture, and while it sometimes has its harsher edges, it is that which guides them through the generations, even if it has its harsh – and from the modern view – cruel traditions. The traditions must be followed if `harmony’ – the `wa’ is to be respected. Modern Japan would find other forms of cruelty it turns out.

In some ways `The Eel’ one of Imamura’s last films is not as powerful as `Black Rain’ or `Ballad of Narayama’ – but the themes are the same in a modern setting. The film begins with a vivid and disturbing scene. A man comes home to find his wife in bed with another. In a fit of rage he kills them both, stabbing them repeatedly with a knife. The `Wa’ has been destroyed in the first few minute of the film. The culprit is sentenced to prison. Like in `Black Rain’ after that shocking opening – the viewer gets all the sex and violence in the film in the first few minutes – the moral issue emerges: in this case the tale revolves not around the victim but the perpetrator of violence. Can a person, after having committed such a heinous act, rebuild his life again, get in touch with his own humanity. Rebuilding shattered lives. Can it be done? How? … That’s Imamura. Well, he’s more than that, but that is the Imamura that touches something deep in the human condition…an awful world, harsh, uncaring, and often brutal… but not without a bit of hope. Not much, just enough to keep him from jumping off a cliff.

Cheers.

___________________

This is a reprint of a part of a long blog entry from 2010 “Oldies But Goodies – Film Reviews: Zinnemann, Fuller, Imamura“

also see Hiroshima Mon Amor